This is the first blog post on the Jordaan Fisheries and Aquatic Ecology website. So it’s fitting to reiterate our vision, articulated on the home page. Aquatic biology and ecosystem science should not respect narrow conceptual boundaries, but by rights should be inclusive. After all, connectivity follows the ambitious yearly migrations of anadromous fish from the head of river systems to the open ocean. Anything that influences a portion of that migratory route at any time may affect the overall water quality, habitat and fitness of the countless species that inhabit the whole—including people.

So we chose “Headwaters to Ocean” as our motto. In collaboration with many colleagues, our portfolio is to examine the complex interactions between human and aquatic systems over different spatial and temporal scales and at different rates of change. Each Jordaan Lab member will take a turn at writing blog posts. Hopefully, different backgrounds and perspectives will flavor each person’s posts, and thus please a variety of readers.

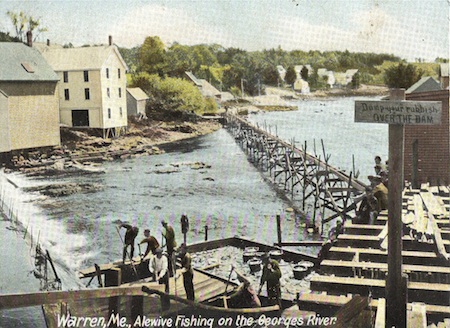

As a historical marine ecologist, I like linking examples from the past to present conditions. The effects of dams on salmon and alewives has been well documented. By preventing anadromous fish from reaching spawning grounds and reproducing, dams have cut into natural population abundance, and may eventually eliminate genetically distinct populations. Here is a postcard from Warren, Maine, around 1900, showing alewife harvesting at the foot of a dam on the St. Georges River (just Georges on the card).

It also shows a fish ladder (nothing I’d try if I were an alewife!), and a sign directing you to “Dump your rubbish over the dam”. The earliest dam on the St. Georges River went in in 1647. Though small, rudely constructed and easily washed out, it was the first of more than 30 dams built on that river by 1900. Yet between 200,000 and 600,000 alewife were taken yearly in Knox County from 1900 to 1905, some of them on the St. Georges River. Life Persists.

Almost 100 years later, the great Edwards Dam was removed on the Kennebec River after much controversy over the wisdom of that action. After all, the Edwards Dam was built in 1837 and no fish population could possibly want to spawn upstream after 162 years! But Life Still Persists. In 2009 more than two million alewives and blueback herring spawned in the Kennebec, the largest run on the Eastern seaboard. This success has encouraged dam removal all over the US. Moreover, Theo Willis at the University of Southern Maine, with colleagues, just showed that alewives and blueback herring are interbreeding. Life Persists in Unexpected Ways. When I get discouraged, alewives make me smile and give me hope.